On the morning of Saturday, August 2nd, I got in a taxi in Erbil, the regional capital of Kurdish Iraq, and asked the driver to take me to the Khazir refugee camp.

This was a scary-ish thing to do.

The “scary” part is a result of the fact that the Khazir camp is outside of the borders of the somewhat autonomous Kurdish region, one of the only secure parts of the country.

The “ish” part comes from the fact that the Khazir camp, though outside of Kurdish borders, is still in an area currently controlled by the Peshmerga—the Kurdish army.

Iraq has been a scary place for a while now, for a number of reasons, but it’s currently scary in italics because of the terrorist group we’ve all gotten to know about in the past three months—ISIS.

So, the cab driver, myself, and our two constricted assholes headed west towards Khazir.

After about 45 minutes, we crossed the checkpoint that meant we were leaving the Kurdish region, and a few minutes later, right when my phone’s blue dot was starting to get just close enough to Mosul for my liking, I looked out the car’s right window and saw the camp:

We pulled in, spent a bunch of time convincing the camp officials and ourselves that I was a journalist, and eventually I was allowed in.

We pulled in, spent a bunch of time convincing the camp officials and ourselves that I was a journalist, and eventually I was allowed in.

I didn’t have a plan, exactly, so I started walking through the long lines of tents, noting that the 118°F (48°C) temperature I had been suffering through all week must be almost lethal here, where the only escape was in a tent.

After a few minutes, I met a man named Kamil who spoke some English, and he invited me into his family’s tent. After talking with him a bit, I learned that it was actually a few families’ tent, and that there were 12 people living in it—five adults and seven children. There was electricity enough for a TV and a fan, and most of the mattresses were stacked on the side.

He told me that 12 people to a tent was common at the camp, and mentioned that his tent was actually about to move to 13, gesturing toward one of the women living there who was thoroughly pregnant.

After a few minutes, I met a man named Kamil who spoke some English, and he invited me into his family’s tent. After talking with him a bit, I learned that it was actually a few families’ tent, and that there were 12 people living in it—five adults and seven children. There was electricity enough for a TV and a fan, and most of the mattresses were stacked on the side.

He told me that 12 people to a tent was common at the camp, and mentioned that his tent was actually about to move to 13, gesturing toward one of the women living there who was thoroughly pregnant.

Kamil was from Mosul, like everyone at the camp. Mosul is Iraq’s second largest city, only 30 miles west of the camp—and as of June 9th, an ISIS stronghold. After taking over, one of the first orders of business for ISIS was rounding up government workers for execution. Kamil, a police officer, was lucky to get out with his family before they got to him. When I asked him if he thought he’d return to Mosul at some point, he shook his head and said, “Fuck Mosul.”

As soon as he learned that I was going to be writing about my time in Iraq, he led me out of the tent to join him on a special Oh Okay Then I Want to Show You Exactly How Upsetting Everything Here Is So You Can Write About It and Tell Everyone Tour.

He walked me past the communal tap for drinking water, and said people used that water to clean themselves too, having not seen a shower since they arrived.

He showed me multiple babies that had been born at the camp.

We popped into a bunch of different tents, one whose fan had been stolen (remember that it’s 118°), and another that had 15 people living in it. He showed me where the shared toilets drain out into a system that flows openly through the camp. He told me that a lot of the families didn’t have enough food and that people were getting sick more and more often and remaining untreated. And these were all people who two months earlier were living their normal lives in their normal homes. Remember the time I complained about anything? That was dumb.

He showed me multiple babies that had been born at the camp.

We popped into a bunch of different tents, one whose fan had been stolen (remember that it’s 118°), and another that had 15 people living in it. He showed me where the shared toilets drain out into a system that flows openly through the camp. He told me that a lot of the families didn’t have enough food and that people were getting sick more and more often and remaining untreated. And these were all people who two months earlier were living their normal lives in their normal homes. Remember the time I complained about anything? That was dumb.

When Kamil introduced me to a man whose two brothers had been executed by ISIS, I assumed that had to be the tour’s horrifying grand finale, but he wasn’t done yet. He brought me into another tent where he introduced me to a woman living there, explaining to her that I was his new writer friend. Without missing a beat, she handed me these:

Whatever I was holding, it was something bad, and I didn’t want to ask what it was. I asked. He pointed across the tent to a little boy and explained that I was holding part of his skull.

Whatever I was holding, it was something bad, and I didn’t want to ask what it was. I asked. He pointed across the tent to a little boy and explained that I was holding part of his skull.

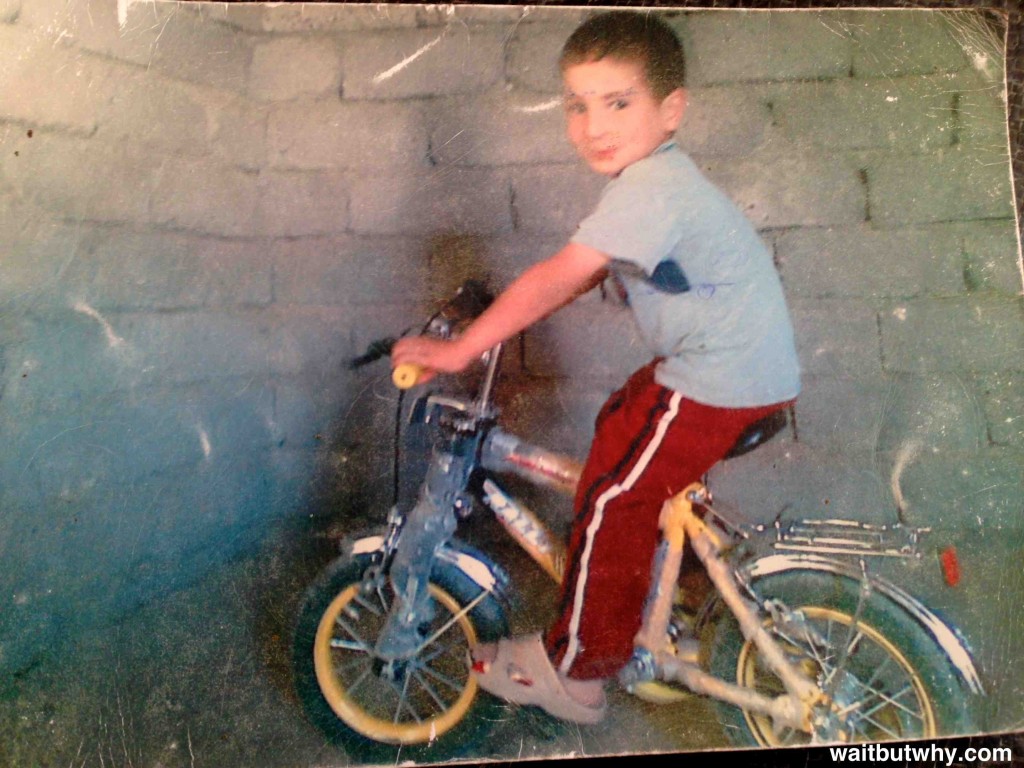

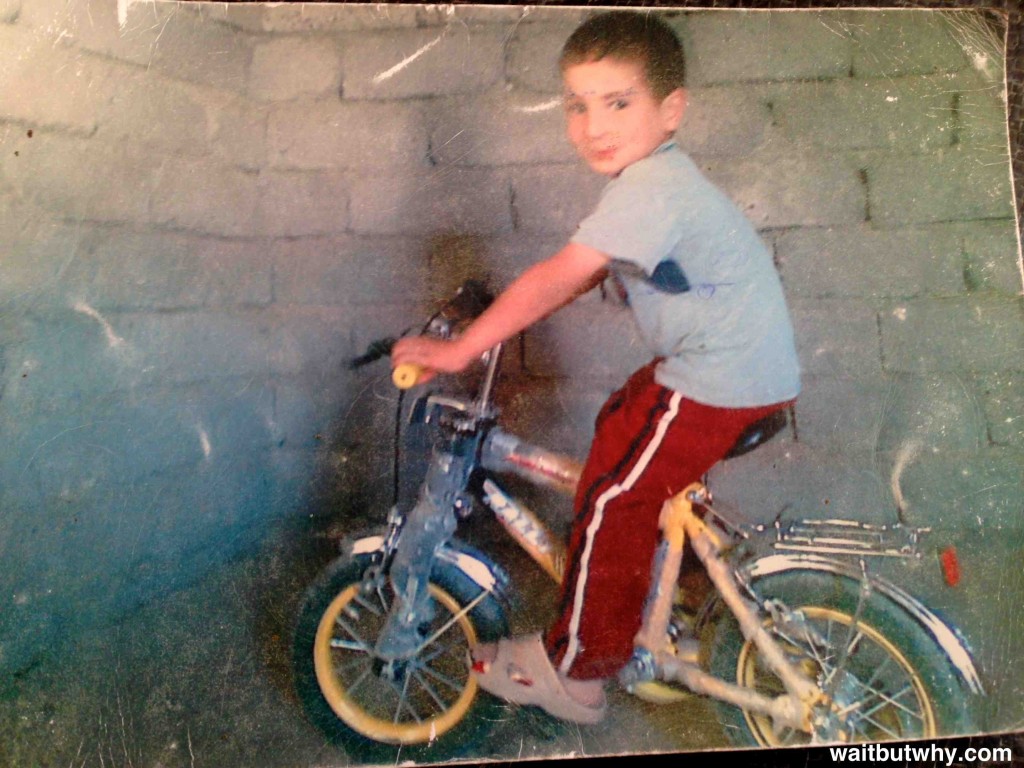

The boy was an eight-year-old named Mohammad. Their family’s house had been bombed in the middle of the night during the first days of the ISIS takeover and subsequent Iraqi government airstrikes. I never learned why or if they were specifically targeted. But the end result was that this healthy little eight-year-old—

—was now this brain-damaged, partially deaf, blind in one eye eight-year-old with digestive difficulties:

The goal of this post will be to understand why this sickening thing happened to this little boy—to reallyunderstand what’s going on in that country—better than you do now.

—was now this brain-damaged, partially deaf, blind in one eye eight-year-old with digestive difficulties:

The goal of this post will be to understand why this sickening thing happened to this little boy—to reallyunderstand what’s going on in that country—better than you do now.

And if we really want to wrap our head around things, we have to start way, way back—in 570 AD.

_______________

Ingredient 1: An Ancient Schism

In 570, a long-named baby was born to a prominent family in Mecca, a city on the west coast of what is currently Saudi Arabia—Abū al-Qāsim Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib ibn Hāshim. Today he’s just known as Muhammad.1 ← click this

Muhammad never had a father—his father died six months before his birth—and his mother died when he was six years old.2 ← again again

After the death of his mother, Muhammad lived with his grandfather, and when he died two years later, Muhammad was transferred to his uncle, a merchant. With his uncle as his mentor, Muhammad became a merchant himself. Not too much is known about Muhammad’s young adult years, but one thing we’re pretty sure of is that he married a 40-year-old widow named Khadijah when he was 25 (he’d have multiple more wives later in his life). They would go on to have four daughters and two sons, only one of whom survived into full adulthood—his daughter Fatimah.

It wasn’t until Muhammad was 40 that his life started getting strange. He had gotten into the habit of going up to a mountain every year for a couple weeks to be alone, meditate, and pray. It was on one of these solo retreats in 610 AD that Muhammad was for the first time visited by the angel Gabriel.3 As the story goes, Gabriel recited messages to Muhammad that were directly from God, which Muhammad memorized. Over the years, Gabriel would continue to visit Muhammad with messages, Muhammad continued to commit them to memory, and later, he would recite the memories to his followers, who would then write them down, and that became the Quran.

Three years after the first visit from Gabriel, in 613, Muhammad began preaching the messages to the public, in his hometown of Mecca. This did not go well. At the time, Mecca was largely made up of polytheistic tribes who worshipped nature-related gods and goddesses, and one of Muhammad’s main messages was that there was one god and any idols to other gods should be destroyed, which was awkward for everybody. People started reacting violently to Muhammad’s growing influence, killing some of his followers, and they may have killed Muhammad too had he not belonged to a fancy family. But in 622, when Muhammad learned of an assassination plot against him, he and his followers decided to bail on Mecca and head to the nearby city of Medina. This journey is called the Hijra in Muslim tradition and it’s celebrated on the first day of the Muslim year.

Muhammad and his followers would spend the next eight years fighting off attempts to destroy them from Mecca and other places, and often being ruthless themselves with those who posed a threat to Islam or refused to convert. The thing a lot of people don’t know is that in addition to being a spiritual leader, Muhammad was, in essence, the general of an army of followers and a tremendously effective strategist in growing and holding on to his leadership position in the face of lots of hostile competition.

Things came to a head in 625 when the Meccans, who were increasingly losing prestige and support as Muhammad’s following continued to grow, launched an attack on Medina and defeated the Muslims. But five years later, Muhammad and a 10,000 man army marched into Mecca and conquered it for good. By the time Muhammad died in 632, Islam had spread through the whole Arabian Peninsula.

The Muslim World Splits

The new Muslim world enjoyed 20 years of internal unity until Muhammad died, and then that was the end of that, forever.

The problem is that Muhammad didn’t appoint a successor before he died, or if he did, he didn’t get the word out to everyone. And because he had no living sons, there was no obvious answer. Here’s what happened:

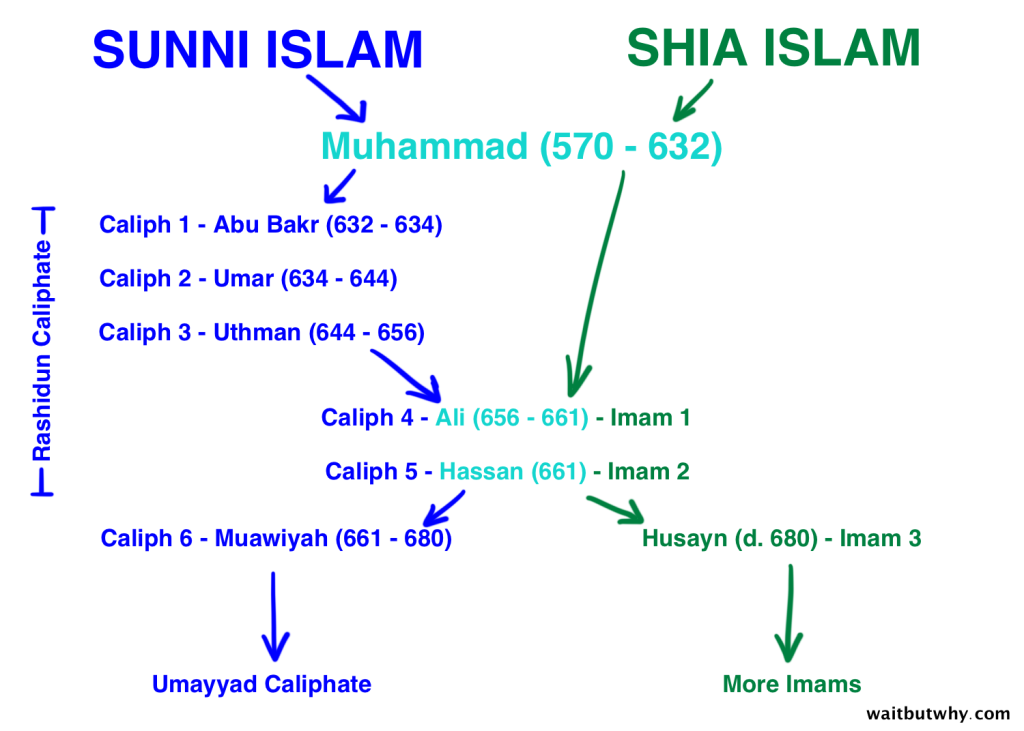

Group A thought that Muhammad wanted the elite members of the Muslim community to choose a fitting leader, or caliph, and whenever that caliph died, the elite would choose the next leader, and so on. And Group A decided a great first caliph to succeed Muhammad would be the father of one of Muhammad’s wives, Abu Bakr (we’ll call him Abu).

Group B disagreed. They thought Muhammad would have told them that only God can choose the successor to lead the Muslim world, and that could only happen by keeping things in the family. To them, all signs pointed to Muhammad’s cousin and the husband of his daughter Fatimah, Ali ibn Abi Talib (Ali).

Group A was bigger and it won.

So father-in-law Abu took over as Caliph, while son-in-law Ali watched from the sidelines and Group B seethed.

When Abu died of illness two years after taking over, another friend of Muhammad’s, Umar, took over, having been appointed by Abu before his death. Umar ruled for ten years before he was assassinated by the Persians he had just conquered. Abu had also appointed Umar’s successor, Uthman, who ruled for 12 years before he was assassinated. All the while, Group B is helpless and frustrated.

But then, the elite decided the next and fourth caliph should be Ali—Group B’s original guy—and for two seconds, everyone was happy.

Five years later, Ali was assassinated, and when his eldest son Hassan became the fifth caliph, he was quickly overpowered by an aggressive rebel force led by Muawiyah, who coerced Hassan out of power and became the sixth caliph—and Group A and Group B would never reconcile again. While Muawiyah was the first of a long dynasty of caliphs, Group B tells a different story. To them, the leaders are more special than merely elected caliphs—they’re divinely chosen imams, and the way they see it, after an annoying three-caliph delay, their first imam was finally in power when Ali got the job. His eldest son Hassan was their second imam, and when Muawiyah kicked him out, Group B threw their support behind Ali’s younger son, Husayn—their third imam.

Husayn, Group B’s third imam, ended up being beheaded by Yazid, Group A’s seventh caliph (Muawiyah’s successor), and so Group B moved onto Husayn’s son as their fourth imam, while Group A continued to ignore Group B and support their caliphs.

This was over 1300 years ago, and yet today’s Muslim world is still completely divided over it, and so much of today’s Middle East strife is centered around this ancient split.

Group A are Sunnis and Group B are Shias.

Today’s Sunni-Shia tensions are about a lot of things, but at their very core is what happened in the 7th century. Sunni Muslims believe in their line of caliphs, and don’t believe them to be chosen by God, and Shia Muslims reject the first three caliphs and instead believe in the line of divinely-chosen imams starting with Ali, revering in particular Ali4 and his son and the third imam, Husayn. Both sects agree that Muhammad is the final prophet, both follow the Five Pillars of Islam, and both view the Quran as the holy book—but Shia are less unquestionably accepting of the Quran in its entirety, because they believe certain parts were recounted by people other than the imams.

Here’s a chart to help clear up all of this confusion:

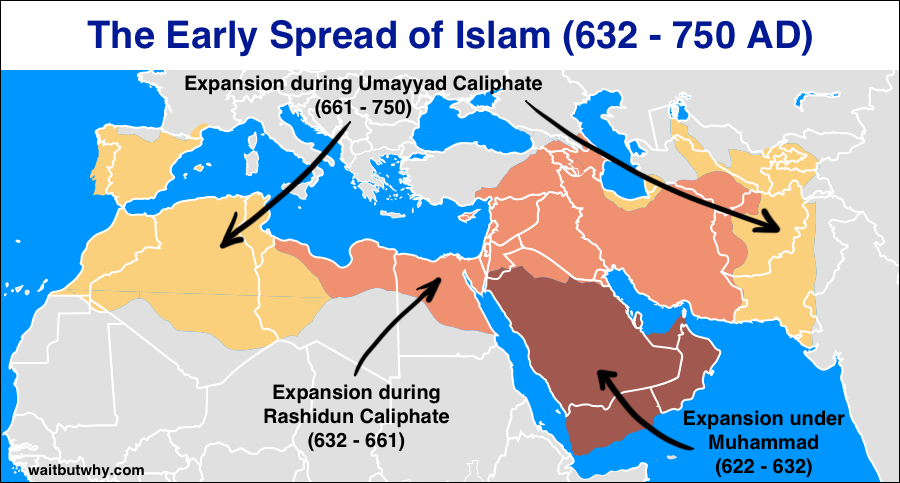

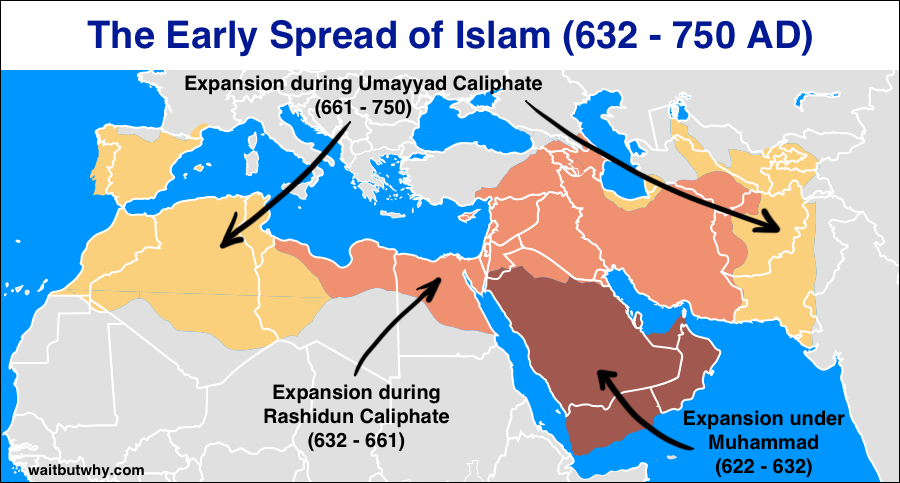

None of this stopped the early caliphs from conquering an insane amount of the world—by 750, just 140 years after Muhammad’s first revelation, the Muslim world had expanded its reach to a large portion of where it exists today.56

But as Islam swept the Earth, this early schism only deepened—it was here to stay.

But as Islam swept the Earth, this early schism only deepened—it was here to stay.

Ingredient 2: Straight Lines

The land of Iraq has the coolest nickname of any land anywhere—The Cradle of Civilization—and for good reason. Ancient Iraqi history is as impressive as it gets. In particular, the fertile strip of Iraq in between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers known as Mesopotamia is often credited with the birth of writing (cuneiform), the invention of the wheel, some of the earliest sailboats, calendars, maps, schools, and the origin of the 60-minute hour and 60-second minute.7 3,000 years later, when Alexander the Great conquered half the world, he chose that land to be his capital, selecting Babylon in particular for its treasures and its critical location between Europe and Asia. 1,000 years after that, the head of the great Abbasid Muslim dynasty built Baghdad on the same land to be the capital of the vast Muslim world, and for the next 500 years (until the Mongols stomped on it), Baghdad reigned as a world hub of learning and commerce and for a time, was the world’s largest city. There may be nowhere in the world with a history as rich as the land of Iraq.

The nation of Iraq, on the other hand, was created by two dicks with a pencil and ruler, and its history is mostly unpleasant.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the land of Iraq had been part of the Ottoman Empire for 400 years.8 There were several ethnic and religious groups on the land, left mostly free to keep to themselves and separate from the others. But when Germany and Co. took on France, Britain, and Russia in World War I, the Ottoman Empire elected to be part of the “and Co.”, which left them ultimately on the losing side. Bye bye Ottoman Empire.

During the war, Mark Sykes of Britain and François Georges-Picot of France got together with a pencil, a ruler, and a bottle of whiskey, and took to the map, carving the Ottoman Empire into nations and determining where their two nations and Russia would get to have spheres of influence after the war if they won.9

Regarding the whole “several ethnic and religious groups” thing and the natural boundaries of separation that had developed between them over centuries, George-Picot famously remarked, “Whatevs,” and with pencil in hand, Sykes is quoted as saying, “I should like to draw a line from the e in Acre to the last k in Kirkuk.”10 Here’s what they came up with:11

The thing about creating borders using a map, pencil, and ruler, is that it’s a terrible way to create borders. If you look at organically-created borders around the world—those that were formed over time by the local populations, based usually on ethnic and religious divisions, and often demarcated by mountains, rivers, or other natural barriers—they’re squiggly and messy. What’s a clear and satisfying straight-line-on-a-map border for imperial powers trying to keep things clean and simple for themselves is a complete disaster on the ground across the world where the actual place is.

When borders are drawn this way, two bad things happen: 1) Single ethnic or religious groups are sliced apart into separate countries, and 2) Different and often unfriendly groups are shoved into a nation together and told to share resources, get along, and bond together over national pride for a just-made-up nation—which inevitably leads to one group taking power and oppressing the others, resulting in bloody rebellions, coups, and sectarian violence. This isn’t that complicated.12

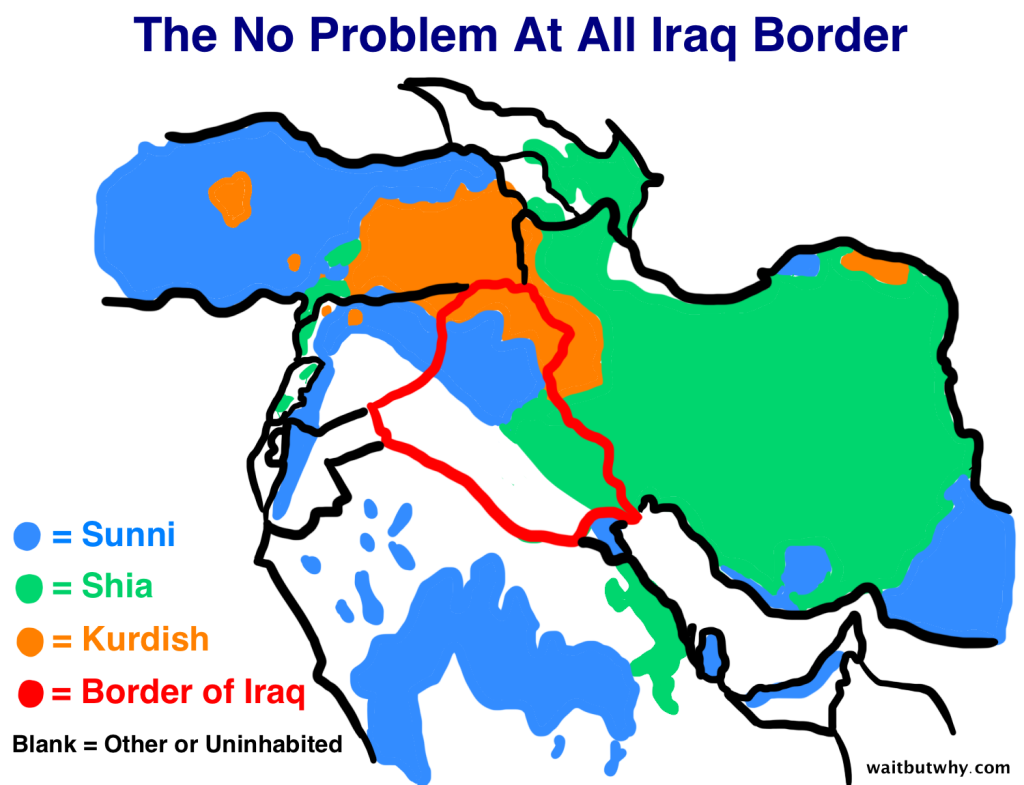

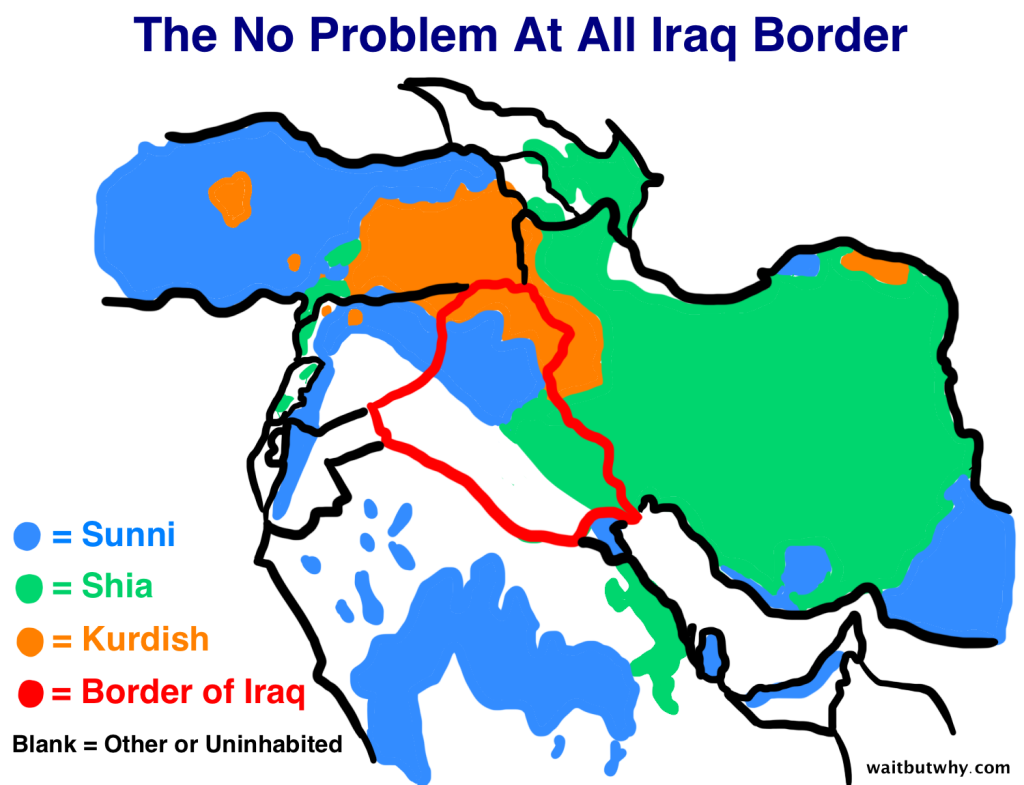

But since it wasn’t really their problem, Sykes and George-Picot just went ahead with it, and over the next few years, precise new borders were drawn, giving birth to modern day Iraq, Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, and Kuwait. Here was Iraq’s new situation:

Can’t see why there’d be any issue here.

Can’t see why there’d be any issue here.

A Tight Lid

For any of you readers considering creating a new, tense nation of ethnic and religious groups who don’t like each other, I’ve been researching this shit all month and I have advice for you:

Your new nation is like a bubbling soup inside a pressure cooker and it’s gonna spew itself all over the kitchen unless you have one critical thing that can keep things in order: a tight lid.

The nation version of a tight lid can be either a strong western occupying power or an iron fist dictator with a scary military machine at his whim—without one of these, your nation will fall apart.13 Email me if you have any questions.14

The new nation of Iraq combined Ingredient 1 (Sunni and Shia Arabs living in the same area) with Ingredient 2 (a border that forces them into a nation together, along with a large group of Kurds) to create a tense pressure cooker.

Things were hot from the beginning, when the new Iraqis revolted against the British occupation in 1920. The British acted as a lid and crushed the revolt. After Iraq achieved independence and the British lid left, a series of military commanders took over the lid duties, stomping a number of revolts and killing each other in coups from time to time. In 1968, the Sunni Ba’ath Party took over, under the leadership of new president Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr and his ambitious vice president and general, Saddam Hussein.

By 1979, Saddam’s influence had grown to the point where he was kind of running the show, and finally he went to al-Bakr and was like, “You know what two cool things are? Murder and retirement. Ya know? I thought maybe you’d want one of those? And you could choose?” and al-Bakr stepped down, bringing Saddam Hussein, the tightest lid of them all, to power.

A lot of things sucked about the 24 year rule of Saddam. He started off in typical dictator fashion, calling together all the senior ranking members of government, and then reading out the names of those who were thought to be disloyal, 22 of whom were later taken out back and shot. He all but legalized “honor killings”—i.e. the tradition sometimes found in places run by Sharia Law whereby a man can kill a female relative if she dishonors her family in any way, without facing criminal charges. And he gave the world Uday Hussein.15

But Saddam’s worst crimes happened during the wars he started and their aftermath.

Worried that the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran would inspire rebellion in Iraq’s large Shia majority, Saddam launched into the eight-year Iran-Iraq War, which killed over 100,000 Iraqis.16 Iraq’s Kurds, who have never wanted to be a part of Iraq, seized the opportunity in the chaos to try to form their own autonomous country, at times receiving support from the Iranians. The attempt failed, and toward the end of the war, Saddam embarked on the al-Anfal Campaign, a systematic genocide of the Kurdish north. One of the worst moments came in 1988, just as the war was winding down, when residents of the city Halabja were overcome by the smell of sweet apples after war planes flew by overhead, and then people and animals started dropping dead all over the city from gas poisoning. The gassing caused more deaths than 9/11. The entire al-Anfal campaign killed between 50,000 and 180,000 Kurds.

While we’re here, let’s pause for a second and talk about the Kurds.

Anyway, back to Saddam, who barely had time to take a shit after the Iran-Iraq War before starting the Persian Gulf War by invading Kuwait for its delicious oil reserves. This, as I learned from my third grade teacher, did not go well for Saddam, and again, Iraq’s oppressed groups, the Shia and the Kurds, tried to take advantage of the situation by attempting to overthrow Saddam. Saddam responded by tightening the lid and crushing the uprisings, killing 80,000 – 230,000 people in the process.19

Saddam was a brutal ruler, but for the most part, under his iron fist, Iraq was a stable country. We all know what happens next.

2003: Off Comes the Lid

Say what you want about the Bush Administration and their decision to invade Iraq and overthrow Saddam, but one thing is for sure: They were very, very wrong when they thought it would be a quick and easy war.

They knew they were removing a lid, but they seemed to think it was off a tupperware container of cookies, not a pressure cooker. And their plan to replace the wrought iron lid with a fresh sheet of democracy cellophane would have worked fine if it were a tupperware container of cookies. Just not if it were a pressure cooker.

So there’s the US, suddenly mired in hell and chaos for eight years, trying to fix a situation they weren’t prepared to fix, and which would ultimately be the Iraqi people’s problem, not theirs. Speaking of the Iraqi people, it’s time for another blue box.

Anyway, as unfortunate as the bloody years of US occupation were for everyone involved, by being there, the US was acting as a lid of some kind. While the US was there, nothing really bad could happen. Then, in 2011, the US left.

A Perfect Storm

Instability is the fertile soil that bad, scary things grow out of, and when the US left, Iraq had a new prime minister, a new government, a new and unfamiliar constitution, and an amateur, recently-trained army—not a stable situation.

The power pendulum had also just swung for the first time in decades. Iraq’s population is 55% Arab Shia, 18% Arab Sunni, and 21% Kurd (with others making up 6%). And despite being the smallest group of the three, Iraq’s Arab Sunnis have been in power over the other groups for almost the country’s whole history. For any living Iraqis, a Sunni government and suppressed Shia majority is all they know. Suddenly, in 2006, Iraq had a new government, led by a hard-line Shia, Nouri al-Maliki. A logical observer of history would probably suggest that it would be a wise move for al-Maliki to be inclusive of Sunnis, regardless of the past, since, as noted above, the country was not in a stable situation. Al-Maliki did just the opposite, arresting Sunni leaders, discriminating against Sunni civilians, and targeting Sunnis disproportionately for torture and violence. All of this exacerbated the instability by making the government less unified and competent, creating rage in the Sunni populous,20 and weakening the loyalty of a military, part of which hates its own government. The anti-al-Maliki feelings are so strong that many normally-peaceful Sunnis find themselves sympathizing or even supporting violent anti-government terrorists.

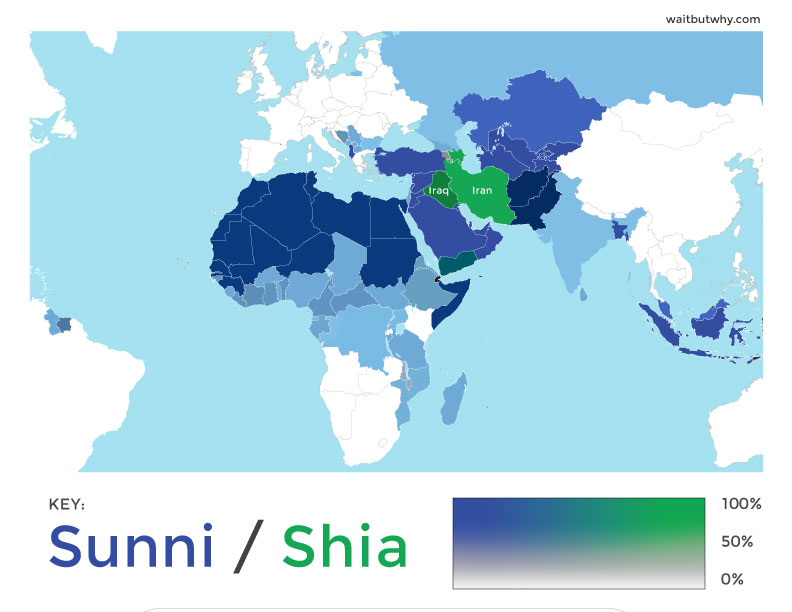

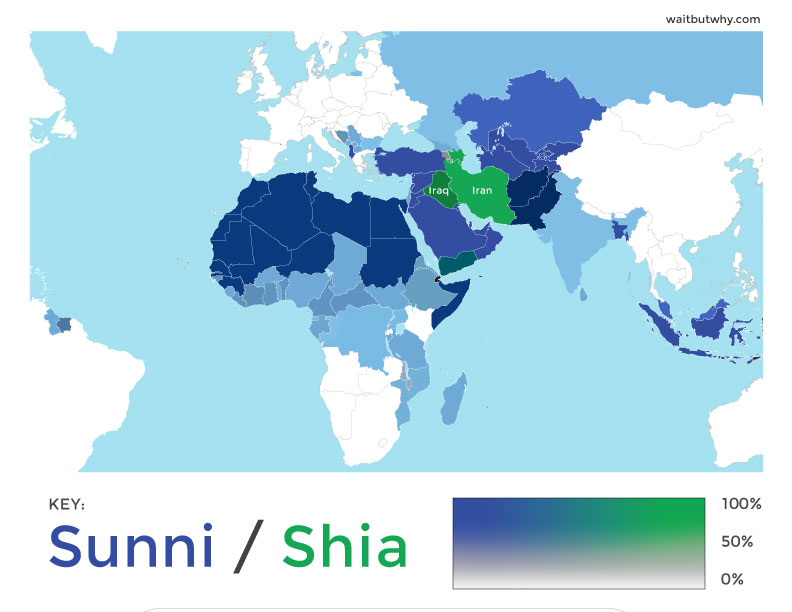

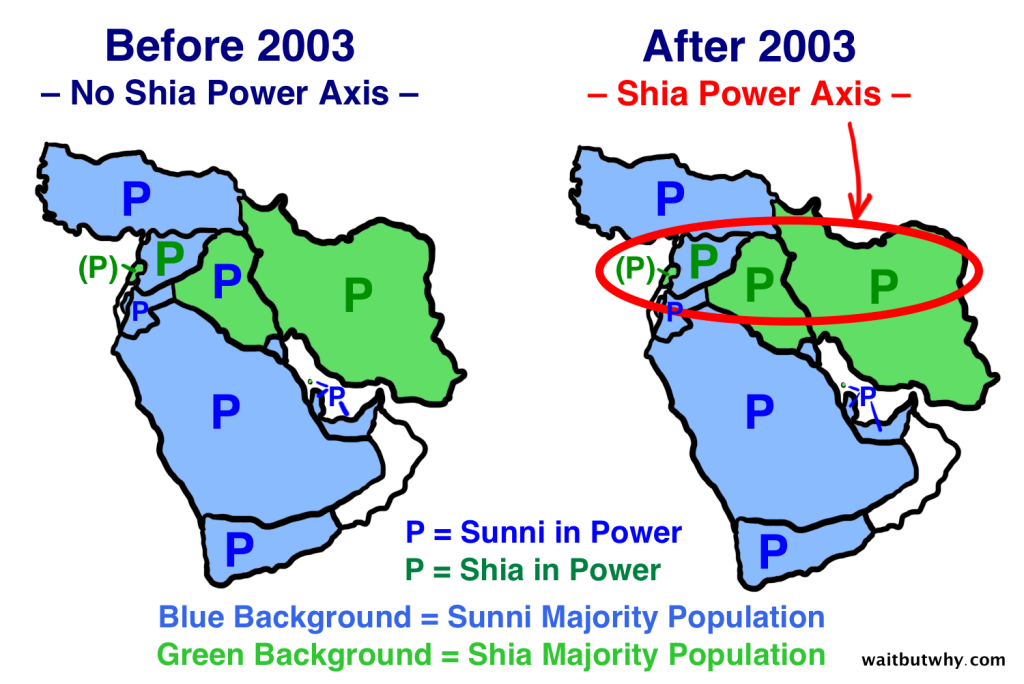

The power switch from Sunni to Shia has broader implications. If you look at the whole world of Islam, it’s clear that Sunni Islam is the vast majority (around 90%) and Shia Islam (around 10%) is just a small side branch:

But when you look at the heart of the Middle East more closely, you can see why things are so complicated.

But when you look at the heart of the Middle East more closely, you can see why things are so complicated.

Here’s what the Middle East looked like when Saddam was in power versus when al-Maliki took over:

Suddenly, Shias are in charge of countries all the way from Iran to the Mediterranean, creating a kind of Shia Axis. This is a great thing for the world’s largest Shia nation, Iran, and it scares the shit out of the region’s most powerful Sunni nation, Saudi Arabia. And what’s been happening is Saudi Arabia and Iran engaging in what is essentially a Cold War, vying for broader power, with conflicts like the Syrian Civil War and the current mess in Iraq serving as proxy wars that can tip the balance in the larger struggle. This is why Iran wants ISIS (a Sunni group) to disappear and why you keep hearing that the US and Iran might actually agree on something (though for different reasons). This is also why the Saudis have been rumored to have funded Sunni resistance movements in both Syria and Iraq, even possibly directing funds to groups like ISIS.21

Yet another factor playing into the trouble is the simultaneous instability of adjacent Iraq and Syria—this creates an unstable border, as well as a situation where the terrorist-fighting front is disjointed and without a shared national narrative to fight for. It also allows a terrorist group to hide in one country from trouble in the other.

Finally, western powers often provide a lid from afar when things erupt somewhere—but in this case, those powers have been gun shy since they just got out of a hideous war in the area and really reallywant to avoid getting involved. Up until Obama’s Mid-September speech, the US has done everything possible to avoid getting involved.

When you add this all together—an unstable and divided new government with an amateur, questionably-loyal army and an angry minority population who feels sympathy for anyone who will resist the government; the interests of a giant neighbor, Saudi Arabia, aligned with a government overthrow; a civil war next door; and a group of western powers who have been determined to stay out—you have the perfect storm for the fiercest of terrorist groups to emerge from the fringe and conquer.

ISIS

The beginnings of ISIS22—a Sunni jihadist group—can be traced back to 1999, when Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a Jordanian jihadist, started the group because he was pissed off about a lot of things. After Zarqawi swore allegiance to al-Qaeda in 2004, this evolved into what became known as “al-Qaeda in Iraq,” and was one of those shadowy insurgent groups you kept reading about the US fighting during the war. When insurgent activity died down after the US troop surge in 2007, ISIS seemed on the decline and disappeared from relevance for a bit.

Al-Baghdadi

In 2010, after ISIS’s second leader was assassinated, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi—a former scholar of Islamic studies23 and a US war prisoner back in 200424—took over and got the group back on track. He replenished their partially-killed-off leadership with dozens of Saddam’s old Ba’athist military personnel, who brought key experience to the group. Then in 2011, when the Syrian Civil War broke out, ISIS joined in as a rebel force25—which helped to train and battle-harden the group. ISIS’s behavior in Syria was so brutal and severe that they even started creeping out the other bad guy groups, including al-Qaeda, who finally had a tantrum in early 2014 and cut all ties with ISIS.

Up until early June 2014, only those who were carefully following the news knew about ISIS. But that’s when everything changed.

On June 5th, just hours after I purchased my non-refundable flight to Iraq, ISIS stormed into the country, taking control of the border, and started systematically conquering towns in the western part of the nation. And suddenly, everyone had heard of ISIS.

Two things were especially shocking about ISIS’s advance into Iraq. First, the horrifying, Genghis Khan-style way they conducted business—i.e. immediately round up and execute all men of authority, in this case anyone who was ever on the government payroll, and then execute anyone else who resisted their takeover.26 Second, the fact that in city after city ISIS attacked, the Iraqi military would flee the scene. This was partially because they were horrified of ISIS and partially because, as mentioned above, the Sunni members of the army weren’t that into fighting against a Sunni group to defend a government they hated. So western Iraq was folding quickly to ISIS, and by June 9th, they had captured Mosul, Iraq’s second biggest city.

The area of Syria and Iraq they had conquered (and are still in control of) is the size of Belgium. Al-Qaeda never conquered anything—they just killed people. So how did ISIS do it? In addition to the perfect storm of factors discussed above, including far more tacit support from masses of civilians than al-Qaeda ever had, ISIS has three qualities that make them so effective:

1) They’re brutal. No regard for human life is a helpful quality when trying to conquer a nation. This Amnesty International report details real accounts of ISIS brutality so scary it doesn’t seem real. An example of an excerpt in the report:

A witness to one such mass killing in Solagh, a village south-east of Sinjar city, told Amnesty International that on the morning of 3 August, as he was trying to flee towards Mount Sinjar, he saw vehicles with IS fighters in them approaching, and managed to conceal himself. From his hiding place he saw them take some civilians from a house in the western outskirts of Solagh:

“A white Toyota pick-up stopped by the house of my neighbour, Salah Mrad Noura, who raised a white flag to indicate they were peaceful civilians. The pick-up had some 14 IS men on the back. They took out some 30 people from my neighbour’s house: men, women and children. They put the women and children, some 20 of them, on the back of another vehicle which had come, a large white Kia, and marched the men, about nine of them, to the nearby wadi [dry river bed]. There they made them kneel and shot them in the back. They were all killed; I watched from my hiding place for a long time and none of them moved. I know two of those killed: my neighbour Salah Mrad Noura, who was about 80 years old, and his son Kheiro, aged about 45 or 50.”

ISIS has officially been the deadliest terrorist group in history. This tool maps out the activity of the world’s most prominent terrorist groups, and when you filter by “Most Victims,” ISIS comes up first, despite being around for less than a decade (their death count is more than double al-Qaeda’s lifetime total). The below screenshot of the tool shows terrorist groups ranked from most total killings (on the top left) to least (on the bottom right). Each mini-chart shows activity over time, with the red and yellow bars representing deaths and wounded, respectively:

2) They’re sophisticated. ISIS functions like a well-run company—it knows how to recruit (ISIS forces are supposedly up to 50,000 in Syria and 30,000 in Iraq), it knows how to fundraise, and it’s incredibly organized. ISIS produces a thorough and professional annual report that details its killings and conquests in the same way a company would report on its revenue and gross margin. Here’s a chilling graphic from their 2013 report breaking down their various methods for the year’s 7,681 attacks:

They’re also pros at social media. Aaron Zelin, an expert on jihadis at the Washington Institute, said thatwhen it comes to social media, ISIS is “probably more sophisticated than most US companies.”

2) They’re sophisticated. ISIS functions like a well-run company—it knows how to recruit (ISIS forces are supposedly up to 50,000 in Syria and 30,000 in Iraq), it knows how to fundraise, and it’s incredibly organized. ISIS produces a thorough and professional annual report that details its killings and conquests in the same way a company would report on its revenue and gross margin. Here’s a chilling graphic from their 2013 report breaking down their various methods for the year’s 7,681 attacks:

They’re also pros at social media. Aaron Zelin, an expert on jihadis at the Washington Institute, said thatwhen it comes to social media, ISIS is “probably more sophisticated than most US companies.”

3) They’re incredibly rich. According to Iraqi intelligence, ISIS has assets worth $2 billion, making it by far the richest terrorist group in the world. Most of this money was seized after the capture of Mosul, including hundreds of millions of US dollars from Mosul’s central bank. On top of that, they’ve taken oil fields and are reportedly making $3 million per day selling oil on the black market, with even more money coming in through donations, extortions, and ransom. ISIS has also gotten ahold of an upsetting amount of high-caliber, US-made weapons and tanks that were for the use of the Iraqi army but left behind when the army fled. They’ve even gotten their hands on nuclear material that they found at Mosul University.

On June 29th, ISIS just fully went for it and proclaimed itself a caliphate—i.e. a global Islamic state—and commanded all the world’s Muslims to obey Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the grand caliph. Those living in ISIS-captured cities are getting a taste of what life in the new caliphate is like:

- Women have about as many rights as a goldfish, barely allowed to leave the house and forbidden from showing their faces in public.

- No smoking ever, and also no tampering with or disabling the smoke detector in the airplane lavatory.

- If they’re not just rounded up and executed on the spot, Christians and other non-Muslims are forced to convert to Islam, pay a hefty non-Muslim tax, become a refugee, or die. The doors of Christian houses are marked with a ن, a symbol that signifies that they’re Christian. Nazi-esque.

- Some reports say a fatwa (an Islamic law ruling by an authority) was issued declaring that all women between the ages of 11 and 46 would undergo genital mutilation, a tradition meant to suppress a woman’s sexual desire in order to discourage “immoral behavior.”27

As for future goals, the short term goal is to establish an Islamic nation in the areas it currently controls, with some expansion of the boundaries. In the medium term, al-Baghdadi has declared that“this blessed advance will not stop until we hit the last nail in the coffin of the Sykes–Picot conspiracy”—i.e. until those pencil and ruler lines drawn after WWI are gone and all the nations are part of the new caliphate. In the long run, ISIS wants to expand its caliphate to the reaches of the first Muslim dynasty in 750 AD, and beyond:

Some people have argued that this map wasn’t made by ISIS, but rather by their supporters. Even if that’s so, al-Baghdadi’s ambitions certainly seem to match, and exceed, those on that map. In July, al-Baghdadi put out a message to Muslims that assured them that ISIS “will conquer Rome and own the world.”

Some people have argued that this map wasn’t made by ISIS, but rather by their supporters. Even if that’s so, al-Baghdadi’s ambitions certainly seem to match, and exceed, those on that map. In July, al-Baghdadi put out a message to Muslims that assured them that ISIS “will conquer Rome and own the world.”

Over the past three months, as ISIS has marched through Iraq, 1.2 million Iraqis have become refugees. 700,000 of them are hiding under the protection of Kurdistan’s Peshmerga army. One of those 700,000 refugees is eight-year-old and now badly-damaged Mohammad, who was living a normal life in Mosul when ISIS attacked.

_______________

Five days after my visit to Khazir refugee camp, ISIS made an aggressive push forward into the scary-ish territory and captured the Khazir camp. The Peshmerga army retreated, instantly converting the area into scary-in-italics territory. That night, a black ISIS flag rose up over the camp where the Kurdish flag had been. Luckily, this happened after a few days of ISIS-Peshmerga fighting, and the refugees had time to run before ISIS arrived. But now, where do they go? People like Kamil, a police officer, cannot go back to Mosul—his name was on the government payroll, and he would be executed upon arrival. But without significant money, many refugees are not allowed into Kurdistan either. Some simply camped out on the road in the searing heat.

A few days later, with the help of US airstrikes, the Kurds recaptured the Khazir camp and a number of other areas ISIS had taken from them.

Since my visit, two new developments offer some hope that things could possibly turn around. The first is that the polarizing Nouri al-Maliki is no longer the Prime Minister. He has been forced out and replaced by another Shia leader, Haider al-Abadi. We’ll see if al-Abadi can cool off some of the Sunni rage al-Maliki’s administration ignited.

The second development happened on September 10th, when President Obama announced that the US would engage in a new campaign of airstrikes, both in Syria and Iraq, to try to defeat ISIS. Airstrikes are sure to slow ISIS down, but to take down and dismantle a group as shadowy, relentless, and fearless as ISIS, I doubt airstrikes will suffice. It’s going to be a lot harder than that.

_______________

And another time, North Korea

Sources

William Montgomery Watt – Muhammad: Prophet and StatesmanWilliam Montgomery Watt – Muhammad at MeccaWilliam Montgomery Watt – Muhammad at MedinaMajid Ali Khan – Muhammad, the Final MessengerBernard Lewis – Islam in History: Ideas, People, and Events in the Middle EastMuhammad Husayn Haykal – The Life of MuhammadRichard C. Martin – Encyclopedia of Islam & the Muslim WorldNPR – Chronology of the Shiite-Sunni SplitPew Research – The Future of the Global Muslim PopulationThe Christian Science Monitor – Cause of Iraq’s Chaos: Bad BordersThe Guardian – First world war: 15 legacies still with us todayCIA World Factbook – IraqThe World Bank – GINI IndexTime – The Sum of Two EvilsSons of SaddamLiam Anderson; Gareth Stansfield – The Future of Iraq: Dictatorship, Democracy, Or Division?Al Jazeera – Islamic State ‘has 50,000 fighters in Syria’Wall Street Journal – Refugee Numbers Grow as Civilians Flock to Iraqi CampsPeriscopic.com – A World of TerrorAmnesty International – Ethnic Cleansing on a Historic Scale: Islamic State’s Systematic Targeting of Minorities in Northern IraqNew York Times – Sunni Extremists in Iraq Seize 3 Towns From Kurds and Threaten Major Dam

Sources

William Montgomery Watt – Muhammad: Prophet and StatesmanWilliam Montgomery Watt – Muhammad at MeccaWilliam Montgomery Watt – Muhammad at MedinaMajid Ali Khan – Muhammad, the Final MessengerBernard Lewis – Islam in History: Ideas, People, and Events in the Middle EastMuhammad Husayn Haykal – The Life of MuhammadRichard C. Martin – Encyclopedia of Islam & the Muslim WorldNPR – Chronology of the Shiite-Sunni SplitPew Research – The Future of the Global Muslim PopulationThe Christian Science Monitor – Cause of Iraq’s Chaos: Bad BordersThe Guardian – First world war: 15 legacies still with us todayCIA World Factbook – IraqThe World Bank – GINI IndexTime – The Sum of Two EvilsSons of SaddamLiam Anderson; Gareth Stansfield – The Future of Iraq: Dictatorship, Democracy, Or Division?Al Jazeera – Islamic State ‘has 50,000 fighters in Syria’Wall Street Journal – Refugee Numbers Grow as Civilians Flock to Iraqi CampsPeriscopic.com – A World of TerrorAmnesty International – Ethnic Cleansing on a Historic Scale: Islamic State’s Systematic Targeting of Minorities in Northern IraqNew York Times – Sunni Extremists in Iraq Seize 3 Towns From Kurds and Threaten Major Dam

Via - waitbutwhy

I am mohammadali and this is a letter for you from leader of Iran Mr,Khamenei..this is the link

ReplyDeletehttp://english.khamenei.ir//index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=2001

please read it and let me know about your opinion.

my email is nabavi.mail@gmail.com