|

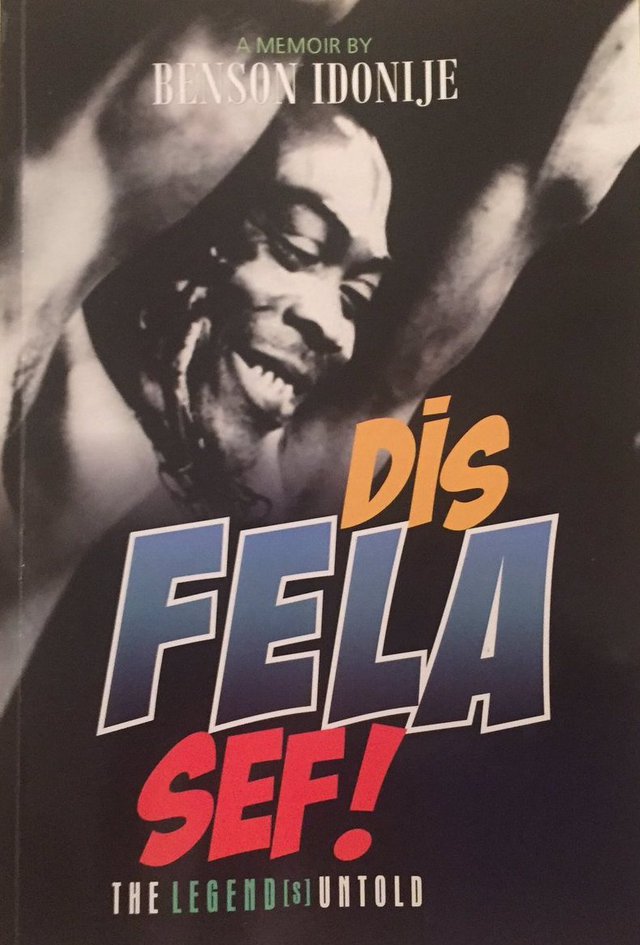

If the legendary Fela Anikulapo Kuti were still alive, he would be 80 years tomorrow. Age would have mellowed him down alright, but his music would continue to evolve mellifluously, reaching out to new levels of creativity, along with the path of Classical African Music which he began in 1986 with the landmark album, Beasts of no nation.

If Fela was still living, he would be ‘looking’ and ‘laughing’ derisively now in utter vindication, at the current state of the Nigerian nation where almost all the predictions he made and the accusations he levelled against successive governments in terms of corruption and bad governance are visibly manifesting themselves. After all, he fought hard to stem this ugly tide – from the 70s to the 90s, using his music as a weapon.

I was watching some of his recorded live performances on the night of August 2, 2018 courtesy of Hip Television, an entertainment channel which has become reputed for direct identification with its target audience in terms of local content: apparently, this special programme was intended to remember the day Fela died in 1997.

I watched with engrossed interest and a feeling of nostalgia the live performance of Don’t gag me, one of those early Afrobeat hits recorded at Luna Club, Calabar in 1973 and was deeply moved by the appearance on stage of the late Igo Chico, the tenor saxophone legend who legitimized the instrument for Afrobeat.

He wailed on the instrument with choruses progressing menacingly and interminably for almost one hour as Fela called out his dancers to the floor in turns.

I also saw the late Henry Kofi, arguably the most creative and percussive conga player in Africa: the vitality of his distinctive rhythmic patterns pushed audiences into dance party ecstasy.

The performance of this song brought home to me memories that are still lingering, but the music that spoke volumes to the political and economic situation of today were Sorrow, blood and Tears and especially Teacher, Don’t Teach Me Nonsense.

These two spoke of corruption, poor governance, mismanagement of Nigeria’s resources, economic slavery and cultural imperialism among many others – as if Fela was still around, driving home the message – with utmost urgency and immediacy. But indeed, the man is still with us, body and soul, considering the inspiring body of work he left behind as a legacy.

It is now 21 years since he departed this earth, but his personality looms large. He seems omnipresent. We speak of him in the present tense; his first name is used not so much to demonstrate personal familiarity as it is to acknowledge the pervasiveness of his influence. Today, Fela’s music is the inspirer of the contemporary hip-hop that is earning Nigeria and Africa all the acclaim and recognition that we enjoy from the international community.

As far back as 1988, trumpeter Miles Davis, perhaps the most influential modern jazz musician that ever lived, a critic and an astute judge of music and musicians predicted that Fela’s Afrobeat would become ‘one of the kinds of music of the world.”

Today, Afro beat bands have been formed all over the world who are drawing from Fela’s overwhelming influence even as musicians and fans lapse into his vocal rasp to make a point. Needless to say that the riffs and phrases he created to establish the culture of Afrobeat have all seeped into today’s contemporary music.

International recognition came posthumously to Fela in a manner that was unprecedented in 2009, courtesy of Bill T. Jones who directed and choreographed Fela! On Broadway. Since then, even record companies in America who were opposed to the long duration of his music for commercial reasons have since embraced Fela’s logic and ideology on his own terms; they are now enjoying the elasticity of African music in his Afrobeat.

But more surprising is the perception of the British scene expressed by Valerie Wilmer, the author of As Serious As Your Life and Jazz People, a renowned journalist – photographer whose views are well – informed and authoritative. Her sentiments are published by The Wire, one of Britain’s most popular and widely acclaimed entertainment magazines.

Fela used to paint the picture of his sojourn in London from 1958 to 1963 as a harrowing experience. He told of the hostility of his various landlords who discriminated against him on account of his black colour; he often narrated how difficult it was to integrate himself into the British jazz scene where he was sometimes rebuffed and despised obviously because he had the guts to play the trumpet where fellow Africans were associated essentially with drumming at the time.

But in acknowledgement of the profoundness of his eventual musical success and the huge legendary posture he now commands, the period of his sojourn in London as a student is being acclaimed as one that soaked up the experience for him as well as prepared the groundwork for his revolutionary Afrobeat.

The four-page story describes him as The Prince of The City, an accolade which is also the caption of the story for reason of the fact that while studying music at Trinity College where he enrolled for piano, trumpet and harmony, he moved through almost all the city’s jazz clubs every night – from Flamingo and Roaring Twenties to Marquee, Club Afrique, Ronnie Scott’s, Iroko Club and more, jamming with musicians whether he was welcomed or not.

He was everywhere – with his trumpet as his most trusted companion. He also led his own personal groups – The Highlife Rakers which paved the way for the first tradition of the Koola Lobitos that also featured Wole Bucknor on piano and Bayo Martins, drums.

He took part in almost all the Nigerian and African entertainment shows and festivals prominent among them, We Speak of Africa concert programme where, in 1962, he attracted attention not only with his music but also his profound confidence and appearance, which many described as a “representation of the modern African.” But perhaps the most historically nostalgic aspect of this account is a reminder that in all of this, Fela made his London stage debut at the Royal Court Theatre, Chelsea (soon after arriving) playing the trumpet in a landmark production of Soyinka’s play, The Swamp Dwellers with the Nigerian playwright, Fela’s cousin on guitar.

The late Banjo Solaru, one of the pioneers of advertising in Nigeria was on hand to help with the readings.

In 1959, Fela’s enthusiastically unrelenting spirit got him back at the court with Soyinka, this time with the legendary Ambrose Campbell as a guitarist. Fela and Campbell accompanied the future Nobel Laureate in dramatised readings of his immigration poems and protests at the French explosion of an atom bomb in the Sahara. He did several remarkable things in London as a student even as he routinely traversed the entire city, moving restlessly through the jazz, rock ‘n roll and R& B subcultures of that period.

Incidentally, this same ubiquitous routine characterised his arrival in Nigeria in 1963 – from the jazz quintet days through to the Nigerian version of the Koola Lobitos years which lasted till 1969: he continued to jam with the various highlife bands in Lagos, among them Roy Chicago at Surulere Night Club; Adeolu Akinsanya, Western Hotel; E.C. Arinze at Kakadu; Charles Iwegbue, Lido Bar and Rex Lawson in 1965 at Chief Osuala’s Central Hotel among others.

It was not until the breakthrough came for him with Jeun Koku in 1971 that this ubiquitous phenomenon stopped – for him to devote all his energy to the consolidation of his new music which was now driven by a pan – African ideology.

At 80, Fela’s legendary posture continues to soar, opening up new vistas and perspectives – even twenty one years after his death: a new accolade has been added to his already over- loaded profile – that of being the Prince of the city of London.

Fela is not only the Prince of the city of London; he is also the Prince of the city of Lagos.

No comments:

Post a Comment